The Intriguing Legacy of the Huastecs: Culture and Conquest

Written on

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Huastecs

The Huastecs, known for their distinctive pyramids and metallurgical skills, were ultimately conquered by the Aztecs. Before the Aztecs established their vast empire, they needed to subdue various cultures across Central America. Among them, the Huastecs stood out as one of the most intriguing groups, speaking a completely different language.

[Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

The Huastecs inhabit the northern regions of Mexico, with a current population of approximately 70,000. Their language, Huastec, is one of only three indigenous tongues still spoken in the country today. Despite the survival of this language, the ancient civilization from which it sprang is often overlooked in discussions surrounding pre-Columbian societies. The Huastec culture, distinct from their Aztec neighbors, was overshadowed and eventually absorbed into the Aztec Empire.

Section 1.1: Identity of the Huastecs

The Aztecs referred to them as "people of the skin," or Huastecs, whereas the Huastecs themselves use the term "Teenek." They find the label “Huastec” to be derogatory. Linguists have long been intrigued by their unique language, which bears no resemblance to Nahuatl, the Aztec language.

The origins of the Teenek language have been extensively studied, revealing that it is part of the Mayan language family—a surprising connection given that the Mayans settled on the Yucatán Peninsula, nearly 800 kilometers away from Huastec territories. It is believed that their migration occurred between 1500 and 100 BC, leading them to the region now known as Huasteca, adjacent to the Totonac territories, another pre-Columbian culture still present today but with limited influence on modern Mexican identity.

Subsection 1.1.1: The Teenek Language

Documentation of the Teenek language began in the 16th century by Brother Andres de Olmos, establishing it as the oldest of the Mayan languages. This differentiation stems from the fact that after their migration, the Teenek lost contact with most of their Mayan relatives. Nevertheless, interactions with neighboring groups, likely including the Totonacs, occurred, although archaeological findings have yet to yield comprehensive insights into the timing and motivations behind the Huastec migration.

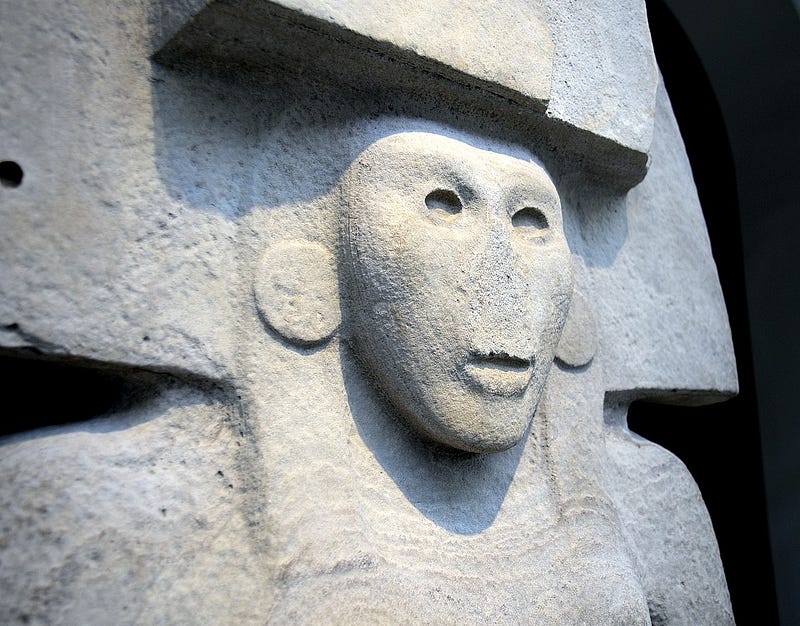

Huastec Ceramic Monkey Vessel — [Photo: Gary Todd, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Section 1.2: The Huastec Civilization

Over centuries, the Huastec people established a robust cultural identity, despite the region's ethnic diversity. Situated on the periphery of Mesoamerican civilization, the Huasteca developed a coherent social structure and a unique material culture, particularly evident in their architecture and sculpture.

Initially, the Huastecs formed independent city-states, which later unified into a single kingdom. By the early postclassic period, around 900 AD, their influence peaked. They were often perceived as a fierce and warlike society, with a notable appreciation for music.

The Huastecs constructed large urban centers and gained acclaim for their intricate patterned textiles. They were also skilled in metallurgy, producing bells—a rarity in Mesoamerica. Despite this advanced craftsmanship, they predominantly relied on stone tools, which suggests a paradoxical coexistence of sophistication within a Stone Age context.

Chapter 2: Huastec Architecture and Sculpture

Section 2.1: Architectural Innovations

A striking feature of Huastec architecture was their circular pyramids, contrasting with the rectangular designs of other Mesoamerican civilizations. The pyramids featured rounded tops, adorned with decorative murals and monumental sculptures. Ruler residences were constructed on elevated platforms, and public buildings for assemblies were common. Many cities were fortified, although archaeological evidence remains sparse due to many unexplored sites.

The city of Tamtok stands out as the best-preserved Huastec site, once serving as the capital of the State of Teenek.

Section 2.2: Unique Sculpture Characteristics

Huastec sculpture exhibits distinctive traits; unlike the Aztecs, who found nudity scandalous, the Huastecs often depicted figures without clothing, reflecting their cultural norms. Accounts suggest they fought in the nude, and their sculptures often display expressive faces and postures—unlike the more subdued expressions found in other pre-Columbian art. Female figures are frequently represented, sometimes with a child depicted on their back, symbolizing life and death.

By the late 15th century, the Huastecs fell under Aztec dominance but retained a degree of autonomy. The subsequent Spanish conquest severely disrupted their social structure. Today, the Teenek people are primarily recognized for their traditional agricultural practices and vibrant cultural heritage.